Andy Lloyd's Book Reviews

The Three Dangerous Magi

By P. T. Mistlberger

Subtitled "Osho, Gurdjieff, Crowley"

O Books, 2011

ISBN 978-1-84694-435-2

$35.95/£19.99

I first got to know the author of this book, P.T. Mistlberger about 10 years ago. We were both members of a wonderful online forum exploring many esoteric subjects. My main focus, of course, was Sitchin, and Mistlberger was researching Zecharia's ideas at the time (more on this in a while). I realised at the time that he had an extraordinary breadth of knowledge, and a powerful intellect to bring to bear. What I didn't appreciate at the time was Mistlberger's deep personal commitment to the path of self-knowledge over many, many years. That journey through the 'Work' of these flawed masters, who make the tri-foci of this incredible book, provides the reader with a viewpoint of exceptional scope and clarity.

The last book of its ilk I read was David Ovason's "The Zelator", to which "The Three Dangerous Magi" compares favourably. That was a long book, too. "The Three Dangerous Magi" is 714 pages long, with the main bulk of the text occupying 603 pages. Yet it is not long-winded. Indeed, it is rather concise! A biography of each of the three subjects would certainly require at least 200 pages, but the content of this work is not simply biographical.

Mistlberger manages to cram in historical and philosophical influences, an outline and critique of their teachings, lengthy analyses of their individual failings, and a practitioner's guide through the Work that each set out. No easy task, let me tell you.

Osho At the

outset, I thought I knew a reasonable bit about Crowley, perhaps a beginner's

understanding of Gurdjieff's place in the esoteric field, and frankly nothing

about Osho. Now I feel like I understand a great deal about each man, and

his work; such was the grand sweep of this magnificent text. Each of these 20th Century Magi is already wrapped in myth,

and Mistlberger sets about deconstructing the popular misconceptions that have

arisen over the years. His insights may be those of an adept - even disciple in Osho's case - but he has a dispassionate air about his writing that

is refreshing, and he's ultimately candid about the human shortcomings of each of

these masters. There is a resolution of opposites in each man. They

explored the personal, as well as the transpersonal. There is a crossover

here between mysticism and group psychotherapy. "Osho, Gurdjieff, and Crowley were

all entirely occupied with healing the inner fragmentation of the person.

To tackle this problem they, on occasion, moved deeply into exploring the Left

Hand path and accordingly ended up using many approaches that addressed the

repressed, shadow part of the mind." (p199) Much of the book is about how these masters built up communes

practising their methodologies, and how these communes disintegrated publically

and spectacularly. Yet, Mistlberger argues convincingly that these

esoteric train wrecks did not reflect on the integrity of the underlying

philosophies deployed by each of the masters. Disciples had their part to

play, and the human fallibility of the masters themselves, too. Their

stories are fascinating, in the same way that all public descents into the pit

are grimly fascinating. Their fallibilities are common to us all, as the

author eloquently describes here: "There is something intrinsically

absurd about the human condition. Nature in itself - inorganic matter and

organic life - moves along as it does, flawless even in its intense

imperfections. But we as humans, being self-conscious, have the capacity

to enter into an exquisitely wise perspective - or more commonly, into a

perpetually awkward and absurd misstep, like a terrible dancer on a floor with

Nijinskys." (p433) A paradox that is returned to again and again throughout the

book is how enlightened men who have crossed the abyss of ego-dissolution could

be so profoundly flawed throughout the rest of their lives. Sex, drugs,

bullying, cars, money. It's all there, writ large across the tapestry of

mystical vision and accomplishment. Yet in a profound way these misadventures

were an intrinsic part of the path to self-knowledge. And it is this

approach that offends the orthodoxy, and threatens the self-righteous. It

is this mystical requirement to walk on the wild side that makes these three men

so dangerous, and compelling.

Crowley Of the three, I think the author is perhaps most overly

sympathetic towards Crowley. I have met enough heroin addicts down the

years to know what that drug can do to them, and like many I find his descent

into depravity is little too much to bear, no matter what inner work was being

accomplished. Mistlberger, perhaps sensing the general reader's unease,

defends his viewpoint: "One of my intentions in writing

this book was to aid in restoring Crowley's reputation to a more rightful

standing. He is, in my opinion, probably the single most unfairly maligned

mystic and teacher of modern times; perhaps a modern day equivalent of

Apollonius of Tyana or Simon Magus." (p418) He argues his case well, arguing that Crowley was not a

particularly good guru, but as a rogue mystic he was second to none, and well

ahead of his time in many ways. He

walked his inner journey with incredible resilience and commitment and - very

unusually - maintained a comprehensive diary of 'unprecedented depth', which he

published, warts and all. By contrast, Osho and Gurdjieff were superb teachers, acting

as transformational catalysts for their disciples. They used strong tactics to

awaken their devotees from slumbering consciousness (Gurdjieff in particular

seems to have run something of a spiritual boot camp). More puritanical

commentators condemned these methods, but you can't make an omelette without

breaking a few eggs. The essential difference between these gurus and

their more orthodox peers is that they advocated immersion in life itself,

rather than withdrawal from the real world, and the inevitable problems of

repression that comes with hiding in a cave, monastery or retreat. Each mystic created a system that was a synthesis of diverse

influences (if Osho's can be said to be a system at all), which Mistlberger

explores in depth in his final chapters. In these chapters the book

contains less personal insights (which form such a stylistic hallmark elsewhere)

and are more encyclopaedic in tone. These chapters, although highly

instructive, extend the book into an overly long opus. Nevertheless, it

should be said that no stone has been left unturned in 'The Three Dangerous

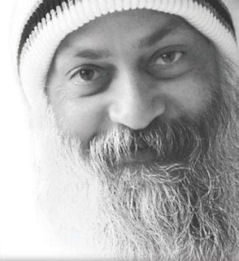

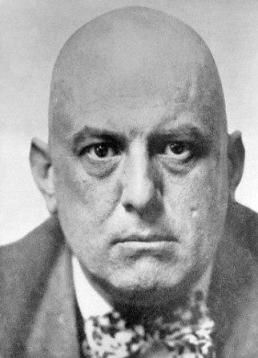

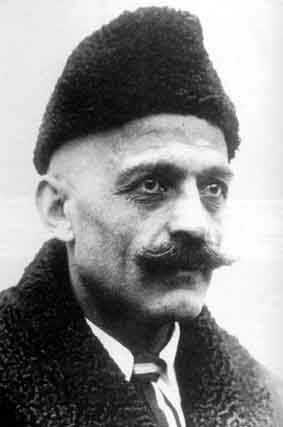

Magi". The only thing the book is missing are images of the three

magi themselves. The author describes them well enough, creating such texture to

their biographies that one feels that one has known each for some time.

Yet that all important visual image is lacking. A set of plates, or some

illustrations, would have been most welcome.

Gurdjieff I mentioned Mistlberger's interest in Sitchin's ideas. In

Appendix III, he explores the remarkable similarity between the 12th Planet

Theory (1976) and Gurdjieff's earlier fictional work "Beelzebub's Tales to his

Grandson", written between 1924-34 (and published in 1950). There's no

indication that Sitchin was a reader of Gurdjieff, meaning that these two

alternative descriptions of the true nature of the solar system emerged

independently. Yet, they contain remarkable similarities: A large planetary body with a lengthy orbit strikes the

Earth early in the life of the solar system, altering its orbit. Visitors from that distant world set up a colony on Earth

to extract resources, and then create humanity as a purely functionary race

overseen by their extra-terrestrial masters. Our true nature is hidden from us, preventing us from

realising our true purpose as a race. A fascinating comparison, from which Mistlberger concludes: "...The main common denominator [is]

that humanity is the pawn of an older race. That is an ancient theme

echoed in many world mythologies, one that can be seen as a powerful metaphor

for Gurdjieff's central idea that in our present state we are incapable of

doing because we are incapable of being. That is, we have no

real free will, and are thus in effect controlled by forces around us.

World myths tend to personify these forces as gods or aliens, but whether these

gods or aliens exist is secondary to the main issue of our own unconsciousness

and inner enslavement." (pp636-7) For a fuller version of this essay see

Gurdjieff, Beelzebub, and

Zecharia Sitchin. "The Three Dangerous Magi" is a magnificent book, the result

of decades of research and personal emersion in the off-beat, mystical worlds of

inner transformation. I can't recommend it highly enough.

Three Dangerous Magi, The: Osho, Gurdjieff, Crowley

The Three Dangerous Magi: Osho, Gurdjieff, Crowley Book review by Andy

Lloyd, 26th April 2011 Books for review can be sent at the author/publisher's own

risk: ![]() You can order your copy through Amazon.com here:

You can order your copy through Amazon.com here:![]() If you live in the UK, you can obtain your copy through Amazon.co.uk here:

If you live in the UK, you can obtain your copy through Amazon.co.uk here:

Andy Lloyd's Book Review Listings by Author

Andy Lloyd's Book Review Listings by Subject

You can keep informed of updates by following me on Twitter:

![]()

Or like my Facebook Page: https://www.facebook.com/darkstarandylloyd